The Poltergeist Murder That Haunted Leslie Abramson: How a Strangled Actress's Death Sparked a Blood Feud That Destroyed Two Brothers

The Curse Was Real

Published on October 10, 2025

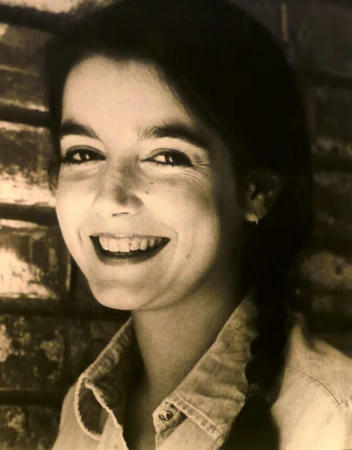

Dominique Dunne, whose promising career was brutally cut short at age 22

The Curse Was Real

On October 30, 1982, the "Poltergeist curse" claimed its first victim. Dominique Dunne, the 22-year-old actress who had captivated audiences as the eldest daughter in Steven Spielberg's supernatural thriller just months earlier, was strangled to death in the driveway of her West Hollywood home. Her killer was not a malevolent spirit but her ex-boyfriend, John Thomas Sweeney, a sous chef at the exclusive Ma Maison restaurant. When police arrived at the scene, Sweeney reportedly confessed immediately: "I killed my girlfriend, and I tried to kill myself."

Dominique was rushed to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, where she was placed on life support and in a medically-induced coma. For five agonizing days, her family kept vigil, hoping for a miracle that would never come. On November 4, 1982, Dominique Dunne was taken off life support. She was just 22 years old, her career barely begun, her life brutally cut short by a man who claimed to love her.

But the tragedy of Dominique Dunne's murder was only the beginning of a story that would haunt Hollywood for decades. At the center of this tale stands Leslie Abramson, the legendary defense attorney who would later become infamous for her role in the Menendez Brothers trial. Though Abramson was not Sweeney's attorney, her involvement in the case would spark a blood feud between two of America's most prominent literary families, a feud so bitter that it would destroy the relationship between two brothers and cast a shadow over the Menendez trial a decade later.

This is the story of how a murdered actress, a controversial lawyer, and a family torn apart by grief became entangled in one of Hollywood's most enduring and tragic feuds.

A Rising Star Extinguished

Dominique Ellen Dunne was born into Hollywood royalty. Her father, Dominick Dunne, was a successful television producer who had worked on hit shows in the 1960s before transitioning to film production. Her mother, Ellen "Lenny" Dunne, came from a prominent family. Dominique's uncle was John Gregory Dunne, the acclaimed novelist and screenwriter, and her aunt by marriage was Joan Didion, one of America's most celebrated writers.

Dominique had inherited the family's creative talents. After studying acting, she landed roles in television shows like "CHiPs," "Fame," and "Hill Street Blues." But it was her performance as Dana Freeling in "Poltergeist" that made her a star. Released in June 1982, the film was a box office sensation, and Dominique's portrayal of the teenage daughter caught in a supernatural nightmare showcased her natural charisma and talent. She had also just completed filming "V," a science fiction miniseries that would air on NBC. Her future seemed limitless.

But behind the scenes, Dominique's personal life was unraveling. She had been dating John Thomas Sweeney, a chef at Ma Maison, one of Los Angeles's most exclusive restaurants. The relationship was tumultuous from the start. Sweeney was possessive, jealous, and increasingly violent. Friends later testified that he had physically abused Dominique on multiple occasions. In late September 1982, Dominique finally ended the relationship and moved out of the home they shared.

Sweeney did not take the breakup well. He began stalking Dominique, showing up at her new home uninvited, begging her to take him back. On the evening of October 30, 1982, he arrived at her West Hollywood home while she was rehearsing lines with David Packer, an actor friend. What happened next would shock the nation.

According to Packer's testimony, Sweeney and Dominique went outside to talk in the driveway. Packer heard arguing, then the sounds of a struggle. He called the police, but by the time they arrived, Dominique was unconscious on the ground, her face purple, her neck bruised. Sweeney had strangled her with such force that he had crushed her larynx. When officers found him, he was kneeling beside her body, sobbing. "I killed my girlfriend, and I tried to kill myself," he told them.

Dominique never regained consciousness. For five days, her family maintained a vigil at Cedars-Sinai, praying for a miracle. But on November 4, doctors informed Dominick and Lenny that their daughter was brain dead. They made the heartbreaking decision to remove her from life support. Dominique Dunne, the bright young star of "Poltergeist," was gone.

Leslie Abramson, whose legal advice would spark a family feud that lasted decades

Enter Leslie Abramson

In the immediate aftermath of Dominique's death, the Dunne family was consumed by grief. Dominick Dunne, who had been estranged from his ex-wife for years, found himself thrust back into her life as they navigated the unimaginable pain of losing a child. His brother John and sister-in-law Joan arrived at Lenny's house to offer their support, but their behavior during this time would plant the seeds of a feud that would last for decades.

John Sweeney was charged with first-degree murder. His defense attorney was Michael Adelson, a public defender, assisted by Joseph Shapiro. The defense strategy was straightforward: this was a crime of passion, not premeditated murder. Sweeney loved Dominique, they argued, and in a moment of uncontrollable rage and jealousy, he had killed her. It was manslaughter, not murder.

As the trial approached, the Dunne family faced a critical decision. The defense team had offered a plea bargain: Sweeney would plead guilty to voluntary manslaughter and receive a sentence of 15 years. It was a substantial sentence, but it was not murder. The question was whether the family should accept the deal or take their chances with a jury.

This is where Leslie Abramson entered the story. Though she was not involved in Sweeney's defense, Abramson was a close friend of John Gregory Dunne and Joan Didion. She was already a prominent criminal defense attorney in Los Angeles, known for her aggressive courtroom style and her success in defending clients accused of heinous crimes. When John and Joan consulted with her about the case, Abramson offered her professional opinion: the Dunne family should accept the plea bargain.

According to sources close to the family, Abramson explained that plea bargains were standard practice in cases like this. A 15-year sentence was reasonable, she argued, and there was no guarantee that a jury would convict Sweeney of murder. The risk of going to trial was that he might receive an even lighter sentence, or, in a worst-case scenario, be acquitted altogether. From a legal standpoint, Abramson's advice was sound. But to Dominick Dunne, it was unthinkable.

Dominick was furious. How could anyone suggest that 15 years was sufficient punishment for the brutal murder of his daughter? How could his own brother and sister-in-law even entertain the idea of a plea deal? He rejected the advice outright. The family would not accept any plea bargain. They would take the case to trial, and they would fight for justice.

But the damage was done. Dominick now associated Leslie Abramson with the defense of his daughter's killer, even though she had never represented Sweeney. In his mind, her advice to accept the plea deal was an endorsement of leniency for a murderer. It was the beginning of a hatred that would consume him for the rest of his life.

The scales of justice that would fail the Dunne family

The Trial: A Mockery of Justice

The trial of John Thomas Sweeney began in August 1983. Dominick Dunne attended every day, sitting in the courtroom and taking meticulous notes. He was determined to bear witness to the last chapter of his daughter's life, no matter how painful. What he witnessed would haunt him forever.

The defense strategy was brutal. Michael Adelson painted Dominique as a troubled young woman who had provoked Sweeney's rage. He introduced evidence of her past relationships, suggested that she had been unfaithful, and implied that she had driven Sweeney to violence. John Sweeney, who claimed to love Dominique, slandered her in court as viciously and cruelly as he had strangled her. Dominick sat in the courtroom, powerless to defend his daughter's memory, as the defense tore her reputation to shreds.

The prosecution, led by Deputy District Attorney Steven Barshop, argued that this was a clear case of murder. Sweeney had a history of violence. He had abused Dominique before. He had stalked her after the breakup. And on the night of October 30, he had strangled her with such force that he had crushed her larynx. This was not a crime of passion; it was premeditated murder.

But the jury saw it differently. On September 21, 1983, they acquitted Sweeney of second-degree murder and convicted him of voluntary manslaughter. The judge, Burton Katz, was outraged. In a rare public rebuke of the jury, he declared that Dominique's death was "a case, pure and simple, of murder. Murder with malice." But his hands were tied. On November 11, 1983, he sentenced John Sweeney to the maximum term for manslaughter: six and a half years in prison.

Six and a half years. For strangling a 22-year-old woman to death. For ending a promising life before it had truly begun. For leaving a family shattered and a father consumed by rage.

Sweeney would serve only three and a half years before being released on parole.

The Blame Game: Abramson in the Crosshairs

For Dominick Dunne, the light sentence was a betrayal of justice. But in his grief and fury, he needed someone to blame. The jury had failed. The judge's hands had been tied. But Leslie Abramson, she had encouraged the family to accept a plea deal. She had suggested that 15 years was reasonable. In Dominick's mind, her advice had been a tacit endorsement of the very defense strategy that had allowed Sweeney to escape a murder conviction.

Dominick began to see Abramson as emblematic of everything wrong with the defense bar. She represented the defense attorneys who used "courtroom theatrics" to manipulate juries, who slandered victims to protect killers, who valued legal gamesmanship over truth and justice. His hatred for her grew, fueled by his grief and his sense of powerlessness.

The trial of John Sweeney transformed Dominick Dunne's life. He had been a struggling writer, living in Oregon and working on a novel that was going nowhere. But during the trial, he kept a journal, recording every detail of the proceedings. After Dominique's death, he turned that journal into an article for Vanity Fair titled "Justice: A Father's Account of the Trial of His Daughter's Killer" (you can read it here). The article, published in March 1984, was a searing indictment of the criminal justice system and a deeply personal account of a father's grief. It launched Dominick's career as a crime journalist and made him a household name.

From that point on, Dominick dedicated his life to covering high-profile criminal trials. He became known for his sympathetic portrayals of victims and their families, and for his scathing critiques of defense attorneys who, in his view, prioritized winning over justice. He always sided with the prosecution. And he never forgot Leslie Abramson.

The Ma Maison Boycott: A Family Divided

In the wake of Dominique's murder, the entertainment industry rallied around the Dunne family. Ma Maison, the exclusive restaurant where John Sweeney had worked as a sous chef, became a symbol of the tragedy. Many people in Hollywood boycotted the restaurant to show their support for the Dunnes. It was a powerful gesture of solidarity, and it had a real impact: Ma Maison's reputation never fully recovered.

But John Gregory Dunne and Joan Didion did not join the boycott. In fact, they continued to dine at Ma Maison regularly, even as the trial was ongoing. For Dominick, this was an unforgivable betrayal. How could his own brother and sister-in-law continue to patronize the restaurant where his daughter's killer had worked? How could they be so insensitive to his pain?

The reports of John and Joan dining at Ma Maison infuriated Dominick. He began to feel that they had abandoned him, that they cared more about being seen at the right restaurants than about supporting their own family. The rift between the brothers deepened.

There were other slights, too. During the days when Dominique was on life support, Joan Didion had retreated to the master bedroom of Lenny Dunne's house and spent hours on the phone with her editor, editing the galleys of her book Salvador. She had used the only outgoing phone line in the house, preventing other friends and family from calling to offer their condolences. When Dominick walked in and found her on the bed, surrounded by galleys, she had looked up and simply asked, "Yes?"

To Dominick, it was a moment that encapsulated everything wrong with "the Didions," as he called them. They were cold, self-absorbed, more concerned with their literary careers than with the suffering of their own family. The image of Joan editing her book while his daughter lay dying haunted him for years.

The Menendez Trial: Old Wounds Reopened

A decade after Dominique's murder, Dominick Dunne found himself covering another high-profile trial for Vanity Fair: the case of Lyle and Erik Menendez, two wealthy brothers accused of murdering their parents in their Beverly Hills mansion. The trial was a media circus, broadcast live on Court TV, and it featured one of the most aggressive and theatrical defense attorneys in the country: Leslie Abramson.

Abramson represented Erik Menendez, and her defense strategy was as bold as it was controversial. She argued that the brothers had been victims of horrific physical and sexual abuse at the hands of their father, and that they had killed their parents in self-defense. It was a strategy that required Abramson to humanize her clients, to make the jury see them as victims rather than killers. And she was brilliant at it.

But for Dominick Dunne, watching Abramson in action was like reliving his worst nightmare. Her "courtroom theatrics," her aggressive cross-examinations, her willingness to put the victims on trial, it was everything he had hated about the defense in his daughter's case. He saw Abramson as the embodiment of a legal system that valued clever lawyering over truth and justice.

Dominick's coverage of the Menendez trial for Vanity Fair was openly hostile to Abramson. He called her "Rastafarian" because of her curly hair, a nickname that was both dismissive and vaguely racist. He questioned her ethics, her tactics, and her motives. He made no secret of his disdain for her.

Abramson, for her part, did not take kindly to Dominick's attacks. She fired back, calling him "the little puke, the little closet queen." The mutual hatred between them was palpable, and it played out in the pages of Vanity Fair and in the courtroom. The Menendez trial became a proxy war for the unresolved anger and grief that had consumed Dominick since his daughter's murder.

But the worst was yet to come.

The Playland Dedication: The Ultimate Betrayal

In 1994, as the Menendez trial was still ongoing, Dominick Dunne received a devastating piece of news. Friends had leaked to him the galleys of his brother's new novel, Playland. When Dominick turned to the dedication page, he was stunned. John Gregory Dunne had dedicated the book to several people, including Leslie Abramson.

It was a betrayal so profound that it defies easy explanation. Dominick's brother, the man who had advised him to leave town during his daughter's murder trial, who had dined at Ma Maison while the entertainment industry boycotted it, who had stood by while Joan edited her book as Dominique lay dying, had now publicly aligned himself with the woman Dominick blamed for his daughter's killer receiving a light sentence.

Pamela Bozanich, the prosecutor in the Menendez trial who had become close friends with Dominick, later said, "It broke Dominick's heart." And indeed, the dedication was the final straw. Dominick was "appalled" at his brother's choice. "It's a curious stand he's taken in light of what's happened to a murdered child in our family," he told reporters. "If that's what he thinks is right, that's fine for him. But not for me. It's not right for me to remain friendly with him."

The dedication to Abramson was not just a personal slight; it was a public declaration. John Gregory Dunne was telling the world that he sided with Leslie Abramson, the defense attorney, over his own brother, the grieving father. It was a choice that would define their relationship for the rest of their lives.

Dominick later wrote in Vanity Fair: "After that my brother and I did not speak for more than six years." In truth, the brothers had already been estranged for years, but the Playland dedication made the rift public and permanent. It was a wound that would never fully heal.

A Feud That Lasted Decades

The feud between Dominick Dunne and Leslie Abramson became one of Hollywood's most enduring and bitter rivalries. Dominick never missed an opportunity to criticize her in his Vanity Fair articles, and Abramson never hesitated to fire back. Their mutual hatred was fueled by more than just the Menendez trial; it was rooted in the unresolved trauma of Dominique's murder and the sense of betrayal that Dominick felt from his own family.

For Dominick, Abramson represented everything wrong with the criminal justice system. She was the defense attorney who used emotional manipulation and legal gamesmanship to free guilty clients. She was the woman who had advised his family to accept a plea deal for his daughter's killer. She was the person his brother had chosen to honor in a book dedication, even as Dominick was publicly condemning her.

For Abramson, Dominick was a self-righteous hypocrite who used his platform at Vanity Fair to attack defense attorneys and undermine the presumption of innocence. She saw him as a man consumed by grief and rage, unable to accept that the criminal justice system was designed to protect the rights of the accused, not just the victims.

The feud played out in the media, in the courtroom, and in the pages of Vanity Fair. It was a clash of worldviews, a battle between a grieving father and a defense attorney who believed in her clients' innocence. And it was a reminder of the deep scars left by Dominique Dunne's murder.

A Brief Reconciliation, Then Death

In 2002, Dominick and John met by chance at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital. Dominick was recovering from prostate cancer; John was battling a failing heart. Alone together, without Joan Didion to mediate, the brothers talked. John called Dominick later to wish him well. "It was such a nice call, so heartfelt," Dominick recalled. "All the hostility that had built up simply vanished. We never tried to clear up what had gone so wrong."

The reconciliation was brief. On December 30, 2003, John Gregory Dunne suffered a massive heart attack and died in his apartment. Joan Didion called Dominick first with the news. He was the first person she told.

Dominick attended his brother's funeral, but the wounds of the past were never fully addressed. The Playland dedication, the Ma Maison dinners, the advice to accept a plea deal, none of it was ever discussed. The brothers had reconciled, but they had not healed.

Dominick Dunne died on August 26, 2009, at the age of 83. He had spent the final decades of his life as one of America's most prominent crime journalists, covering trials and writing novels that explored the dark underbelly of wealth and privilege. But he never forgot his daughter, and he never forgave Leslie Abramson.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Pain and Division

The story of Dominique Dunne's murder is a tragedy that extends far beyond the young actress's death. It is a story of how grief can consume a family, how a single act of violence can ripple outward and destroy relationships, and how the criminal justice system can fail to deliver the justice that victims' families desperately seek.

Leslie Abramson's role in this story is complex. She was not John Sweeney's attorney, and her advice to accept a plea deal was, from a legal standpoint, reasonable. But to Dominick Dunne, she became a symbol of everything he hated about the defense bar. Her dedication in John Gregory Dunne's novel was the ultimate betrayal, a public declaration that his own brother valued his friendship with a defense attorney over his loyalty to his family.

The feud between Dominick Dunne and Leslie Abramson is a reminder of the deep divisions that can arise in the wake of tragedy. It is a story of how personal pain can become public spectacle, and how the search for justice can sometimes lead to more suffering. And it is a testament to the enduring power of grief, which can shape lives and destroy relationships long after the initial tragedy has passed.

For those interested in exploring more about Leslie Abramson's controversial career, we encourage you to read our in-depth analysis of her role in the Menendez Brothers trial. Her legacy remains one of the most debated in American legal history, and her connection to the Dunne family tragedy is a chapter that has been largely forgotten, until now.

To learn more about other legendary defense attorneys and their complex legacies, visit our Advocacy Legends page, where we explore the careers of figures like F. Lee Bailey and Geoffrey Fieger. And if you have thoughts on this tragic story, we invite you to share them on our Contact Page.

The Poltergeist curse may have been a Hollywood myth, but for the Dunne family, the horror was all too real. And for Dominick Dunne, the ghost of his daughter's murder, and the woman he blamed for letting her killer go free, haunted him until the day he died.

References

- Hofler, Robert. Money, Murder, and Dominick Dunne: A Life in Several Acts. University of Wisconsin Press, 2017.

- Dunne, Dominick. "Justice: A Father's Account of the Trial of His Daughter's Killer." Vanity Fair, March 1984. Available at: https://archive.vanityfair.com/article/share/d0d8b06b-0b89-410b-810e-0fcc8a0745d0

- "A literary feud for the ages: What fueled the bad blood between Dominick Dunne and 'the Didions.'" Salon, April 16, 2017. Available at: https://www.salon.com/2017/04/16/a-literary-feud-for-the-ages-what-fueled-the-bad-blood-between-dominick-dunne-and-the-didions/

- "What Happened to Dominique Dunne?" Town & Country, September 28, 2024. Available at: https://www.townandcountrymag.com/leisure/arts-and-culture/a62334020/dominique-dunne-death-explained/

- "Slayer of Actress Sentenced To 6 1/2-Year Maximum Term." The New York Times, November 13, 1983. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/1983/11/13/us/slayer-of-actress-sentenced-to-6-1-2-year-maximum-term.html

- Killing of Dominique Dunne. Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killing_of_Dominique_Dunne